Music Lessons in Composition - "Melodic Motives & Development"

Learn how to write music in the traditional AABA song format

Music Lessons in Composition - "Melodic Motives & Development"

- contributed by Ryan Cullen

So what is it exactly that makes a composition a solid one? Besides having interesting ideas and a smooth progression, one of the most important things is the development of your ideas. It’s within the development of your initial ideas/motives that true unity within your composition can be achieved. It’s the purpose of this article to examine (in the traditional jazz “song style”) the mechanics of melodic motivic development.

To demonstrate some approaches to motivic development in composition, we’ll take a look below at a lead sheet of one of my pieces, “Spring Ahead.”

The basic form of the tune is A, A(1), B, A(1) meaning that it is set in four sections. The first A is 16 bars, the second A is almost exactly the same but has some variation and ends up as only 14 bars. The bridge is the B section (16 bars) and breaks away almost completely (as it should) from the initial motives...but not that much! Finally, there’s a return to the A(1) section and a coda.

Example 1:

TWe’ll begin, obviously, in the first “A” section and look at the 2 primary motives. IT IS UPON THESE MOTIVES WHICH THE MAJORITY OF THE COMPOSITION WILL BE BASED. Notice from measures 1-4, we have motive #1, and from (including pickups) measures 5-8, we have motive #2. Already within bar 6, I began to develop motive #2 by “augmenting” or “making longer” the rhythm from the pickups in measure 4. You’ll notice the same half step relationships between the eighth note pickups to measure 5 and the quarter note triplet in bar 6.

In bar 7, I used the same starting tone as in measure 5, the 9th, this time changing up the rhythm slightly but still keeping the general “character” of bar 5.

EX. 1

Example 2:

In measures 9-10, we see somewhat of a return to motive #1. Here I’m using the same rhythmic motive with the pitches altered. Through the maintenance of this same rhythm, though the pitches are different, a unity within the structure of the piece is achieved. The same holds true for measures 11-12…this area is based on a development/extension of motive #2. Bar #14 can be thought of (to an extent) as a development of motive #1, BUT it has the complete triad within it that distinguishes it quite a bit. It’s probably best to call this motive #3. Remember this motive for later...we will briefly abandon it here, but it will return!

Finally, bars 15-16 can be thought of either as a new motive entirely, or better yet, a “diminution” or “squashing together” of the “key” tones of motive #1…C, F, A.

EX. 2

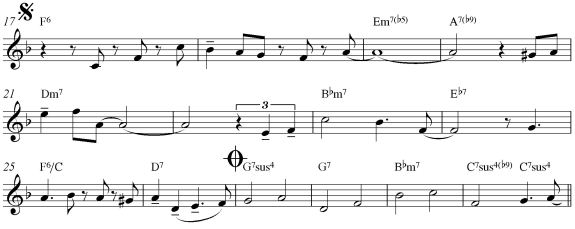

Example 3:

Here we are now at the second “A” of the tune, “A(1).” You’ll notice right away that bars 17-23 are almost exactly identical to the first 8 bars of the first “A.” While some writers will make them exactly the same, and that’s perfectly fine as there are many great tunes that follow that protocol, I find it a bit more interesting to try and change the second “A” up just a little. Here you’ll notice that I’ve just modified the rhythms a bit. In bars 20 and 22, I simply subtracted notes leaving rests. When writing, don’t be afraid to subtract. Rests can be just as important as notes! In bar 25, you’ll probably notice a new motive, #4. In bars 26-30, we return to more of the “developed” motive #2 which we modulate to lead us into the bridge.

EX. 3

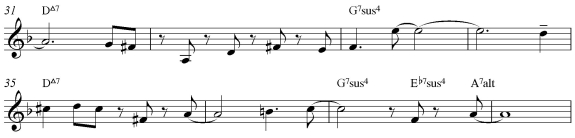

Example 4:

We are now at the “B” section or “bridge.” It’s time to experiment with some new ideas/motives. Though, do we really need to come up with many completely new ideas? While we want the bridge to sound fairly different than the “A” sections, it’s a good idea to first go back in the “A” sections and ensure that all of the motives there were fully utilized. If you recall, two of the motives in the “A” sections were only briefly stated. Those were motives #3 and #4. Therefore, with a little development, creation of one final motive, and a combination of all the aforementioned, we’ve essentially already written our bridge!

Motive #3 starts us out from bars 31-32. Notice the complete triad. We then add motive #5 in bars 32-33. In bar 35, I grabbed motive #4 and then combined it with motive #2 and the “diminished” motive #1! So, while this isn’t completely new material, it’s varied quite a bit to produce a different section, and there’s definitely a great deal “tying” it all together.

EX. 4

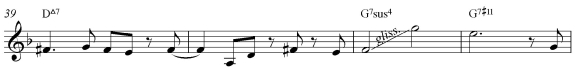

Example 5:

At bar 39, you can clearly see that we’re back to motive #4 and then add motive #3 in bar 40 and finally add a developed motive #5 in bars 41-43. For something completely different in bars 43-46, I added several rhythmic kicks to get us back to the final “(A1).”

EX. 5

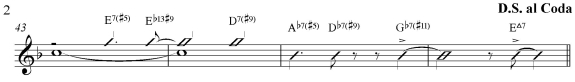

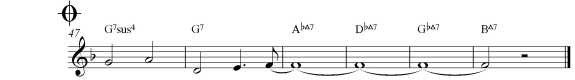

Example 6:

Finally, the Coda takes us back to an even further developed (harmonically) motive #2.

EX. 6

As you can see, motivic development is a key to composing in the jazz “song style” format. It’s not enough to have good ideas…you must develop them, combine them, and really use them to the fullest extent (without, of course, going overboard and becoming minimalistic)!